|

|

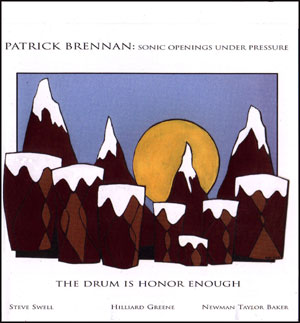

cimp 305 - patrick brennan: sonic openings under pressure

the drum is honor enough

producer's notes

Over five years have passed since the last time patrick brennan (1954, Detroit, MI) last graced the Spirit Room in September of 1998. I would have guessed it to be less than half that time, partly because the experience is still vivid for me, but even more so because every time I renew my contact with the music from that duo session (with bassist Lisle Ellis) I am invigorated by its freshness. Good art?allowing for its subjectivity?maintains that quality of renewal. In that meantime, patrick has played around, released a collaboration with the Gnawan (Morocco) musician M'allim Najib Sudani on deep dish records and a set of live festival music on Cadence Jazz Records.

It was the festival material that directly led to this date as not only was I taken by the power of the group that included Hill Greene (1958, Logansport, IN) and Newman Taylor Baker (1943, Petersburg, VA), Juma Santos Ayantola (1947, Cape Cod, MA) but I also felt that, given the advantages of time and The Spirit Room, it might be very productive to record them on CIMP. The addition of Steve Swell (1954, Newark, NJ) would not only make for a good blend, but would further help guarantee the finest in creative discovery.

The group arrived midafternoon, following a previous night's gig, in seemingly good spirits. Extension boards to hold what appeared to be 3-foot spreads of music were produced during the sound check, arousing my usual apprehensions about the possibility of the notes interfering with the music and, in addition in this case, in part baffling the sound. As it turns out, it is often the music that is baffling in its series of angular turns, breaks, space, and interlacing improvisations. It is the kind of music that inevitably benefits from two takes: one for structure, the second for integrations of individual spirit. Much of this music is orchestral and, in fact, shadow doing sounds at times like it is being executed by a rather sizable orchestra that at the same time contains a comfortably conversant improvising quartet.

The nature of this music necessitated a certain amount of run-through and fine tuning and by 10 p.m., after 2 hours of playing, only 2 pieces (hot red / shadow doing) had been fully addressed. Rather thantedious, the coordination of the music and spirit evolved as a result of rather conversational discussions led by patrick, who talked the music almost as a story with interjections and clarification from the group. patrick clearly knew the course and the group seemed involved and respectful in the challenge of interpretation. And the rundown and strategy sessions could be long. On rough hue it was over an hour before even the first take was addressed. But when it happened, the take was smooth with the predetermined and the improvised falling complementarily into each other to form the whole of this episodic piece.

After rough hue it was decided that the recording part of the evening would conclude but the group would continue the musical discussion, this time in regard to permeations gumvindaboloo, which would be part of the next day's recording. Interesting watching an intellectual and technical discussion metamorphose into emotive music. The process thus far had been so successful that it gave me confidence and enthusiasm for the next day's recording. gumvindaboloo, judging from the discussion, was still very much a work in progress. New approaches and structures were being invented to mesh with parts previously displayed publically in concert. Once more I am reminded that there are as many variations to the process of this music as there are voices in the music, and often the process itself is as interesting as the music is rewarding.

The

next morning, after having worked on gumvindaboloo for at least 1 hour

the night before, the group worked on drums not bombs for about 3 hours

before we began the formal business of recording. Again, even without

breaks, the mood was relaxed, focused, and conversational with

not a discouraging utterance or sense of tedium, even with the repetitious

execution of various musical configurations that make up the compositional

foundation of the piece(s).

The second day's recording sessionopened with drums not bombs and all

the fragments of the past 3 hours came together naturally and wonderfully

as a whole and soon ventured off into Newman's conversation which, consciously

or unconsciously, tips its hat to Max Roach. Newman calls it genetic memory,

"That's just the way I hit." Coincidentally, patrick intoned

that he had had Max in mind when he first began composing the piece. The

first take was good but I think the group was still on delay, still digesting

the 3 hours of rehearsal. The second take (issued here) noticeably renewed

itself in focus and clarity of attack.

Finally they got to gumvindaboloo, a piece in 4 parts, some of whose parts and multirhythm time signatures had the effect of giving me audio illusions of stumbling and acceleration. We finally brought the rather protracted session to a close in the late afternoon and I was impressed not just by the effort and the resultant music but also by the continued resilience of the musicians who, with hardly a break between breakfast and supper, maintained their sharpness, energy, and pride in their musicianship. patrick chose well and the group delivered.

Robert D. Rusch - February 18, 2004

patrick

brennan can also be heard on CIMP 187

Steve Swell can also be heard on CIMPs 108, 116, 149, 156, 184, 203, 207,220,

223, 227, 237, 256, 261, 264, 268, 272, 285, 292.

Hill Greene can also be heard on CIMPs 128, 170, 280.

Newman Taylor Baker can also be heard on CIMPs 103, 159, 273.

the

drum is honor enough

BACK

TO TOP

artist's notes

It’s a treat to visit the Cadence Building and the Spirit Room once again, way up here in the northern fringes of Longhouse Country. My respects to the Haudenosaunee, who are the land’s guardians, and to the gracious and generous CIMP crew.

the drum is honor enough is my 4th recording of new original compositions for my group sonic openings under pressure, which also include which way what (1995), molten opposites (1983) & introducing:soup (1981).

There’s only so much any one improviser can do to affect the total shape of what’s going on in music while it’s being played. I prefer relating with music at the scale of the whole ensemble. One way of doing this is to organize a common area of focus for everybody in the band, and that would be a composition.

Composing for improvisers isn't like the euroclassical procedure, where the creative action, for the most part, is all over before the music’s even been played. A composition for improvisers has also to do everything from tease through kick musicians into doing something new themselves, which makes this closer in function to the relationship dance music has with dancers. Likewise, it’s as much theatrical scripting for multiple protagonists as it is sound coordination, with a composition acting as instigator, mediator, provisional constitution, provocateur, antagonist and adviser.

In practice, composition is really just a slower species of improvisation, and is also an awful lot more than just tune writing. What a composition does, at it fullest, is to reconsider, redefine and renew all of the musical elements. What this can do is renovate the underlying assumptions that improvisers are working with, help to stave off cliché, intensify ensemble concentration, and raise the level of improvisation from a solo/individualist orientation to a more comprehensive and inclusive one.

What I’ve been attracted to is the challenge of creating a coherent musical world out of my own experiences, questions and aspirations. We live with enormous complications that push us in favor of fragmentation, collage, pastiche and eclecticism in art; but - as is nearly any selected image - art is also advocacy for a point of view, a way of responding to experience, and even a proposal for how we might be. I’d like to think that there’s a way to integrate multiplicity, disjuncture, complexity and contradiction into some kind of form that can, all of a piece, get right down into the reflexes and translate into how people can move with what happens (which is also not such a bad definition for what a groove is...).

When I’m involved with music, I keep looking for that sound that’s just around the corner, the one that’s just slightly out of earshot and would somehow brighten and open up a sonic adventure. I try to get below surface appearances such as styles and genres and get down to what’s happening with musical elements at the molecular, or even subatomic strata, before patterns and such are definitively formed, not to do some kind of scientific analysis, but in order to figure out how and why certain musical constellations get to me the way they do, and then to put it all back together, but in my own terms.

I’m fascinated with music’s connective tissue, with how sounds congeal into images, with how those images dissolve and shift, and with how musicians associate sounds, ideas and moves. I also pay attention to blurred shapes of music heard at a distance, mishearings, mistakes, distortions of memory, color, shape, misinterpretations, density, line, how a young kid sings a song and leaves out a phrase, texture, how music might sound to someone who doesn’t care at all about Bb. My concern is always with the sound intertwined with the musical thinking and attitudes active at the heart of generating music.

For me, compositions tend to accrue gradually, piece by piece, in a kind of speculative trial and error sort of dialogue that can often extend over years, with each developing its own concepts, personality and demands. Just like the silences that house music, I can savor the (almost always too long) moments between performances where I can ruminate and turn over and over what’s going on in the music.

Thanks particularly to Elvin Jones, West Africa, the late medieval Europeans and Detroit’s CJQ, I seem to have developed this taste for orchestrating melodically - throughout an entire ensemble - the kind of multilevelled relationships that are happening with percussive polyrhythm; and collective improvisation is in many ways also a theatrical personification of polyrhythmic dynamics.

Even a trio of percussion, strings and wind can be treated as an orchestra with the bass (and turn it up if you don’t have a fancy sound system) acting as the pivotal amphibian voice between drums and wind. As I continue shifting the point of view in and around what can feel like a sonic sculpture, one perception can lead to another, and a composition might grow new limbs again and again, and then again.

I also have an interest in the overall form a listener’s experiencing. Wider time spans, where ideas can develop gradually over the full expanse of a piece of music especially intrigue me. Some of the commonplace features of some conventions push me to try to find something else: unframed open forms tend toward an entropic monotony, especially in terms of variability in texture; theme-solo-theme formats seem to be usually a bit too glib and automatic (besides, what stories really are the same at the end as at the beginning?); I also don’t see why every solo voice has to be working in the same setting. These aren’t in any way exceptionally new issues, but they do give me a few ideas here and there.

Anyone who’s counting on a farmer for food is living interdependently; and all those master race telescreen prompts about self-levitating bootstraps and heroic conquistadors ignore that no matter how much can only be done by oneself, there’s no way it can all be done by oneself. Music itself is a social cooperation par excellence, as the sounds become music because of the web of relationships among people and sonic images. Each composition initiates and depends upon a community of musicians, and the more singular a composition is, the more specific its community is likely to have to be.

For a composition, there’s a whole thicket of communications that have to be traversed along the way to coordinating the kind of shared understandings that would enable anyone in the group to lead the band, or would enable an ensemble to segue intact like a flock of birds. As Marlon Zapata put it, “A strong people don’t need a strong ruler.” There are natural complications such as the word “green” connoting a different shade for each person who hears it; and a composer might even have to invent a distinct language for each person, calling “east” “SSE” for one musician, but “NE” for somebody else. Trial and error, along with experience by means of the music itself, build up the necessary ensemble trust, while there’s a reciprocal influence on the composition in terms of refinements, clarifications, expansions and further developments.

Beyond the dedication of musicians themselves, any music’s going to flourish only in proportion to the health and welcome of its social environment. It’s clear that there are exquisite and masterful musicians because you can hear some of them right here on this disc; and there’s real, but often beleaguered, grassroots support for these musicians. When we were doing some concerts in preparation for this recording, some of the presenters had to go some extra distance just to make the performances viable. One routinely pays bands out of his own not so deep pocket, while his friends help out by hosting musicians for the night in their homes. An art center has to count on just one well-off person to subsidize their concert series as public funding continues to vanish; and at another, the volunteer coordinator homecooked some dizzilicious chili and cornbread in order to supplement the lack of a food budget - and these were not door gigs, either.

The inconvenient truth about music itself is that it’s, in reality, too free to be owned, bought or sold, which makes it, at the very least, pretty awkward as a commodity. Niether griots, Beethoven nor Mingus have had it that easy. The motives behind making music - and it’s social functions: medicinal, restorative, visionary, formative, instructive, re-creative, even ethical - are too complex to efficiently serve simple mercantile purposes. As Bechet put it so well, “The music ha(s) to reach straight out to life and to what a man does with his life when it finally is his.”

And, it’s astonishing just how many times in a row “yes” has to happen for there to be some music, as almost any break in a very fragile chain of recognitions and exchanges - a slipped synapse, a dropped beat, a missed rehearsal, an impenetrable gatekeeper, a canceled gig, a thin budget- can blow an entire initiative, or at least tie one or both hands behind one’s back. The most vulnerable link is sustaining the actual human beings that make music possible. Music may be free, but musicians themselves work very hard for it, and they have to eat too.

As Bill Mollison, the permaculturalist, more or less put it, “Money is to social activity what water is to agriculture.” Here in the “richest and most powerful nation in world history” it’s become an achievement just to get real news and information - and if the conditions of journalism are that sad, you can forget about the arts. Even the best efforts to support the music and expand its community has too often got to face up against that slippery sisyphusian slope of coming up with enough money to keep the musicians and the music together beyond ad hoc slam bam hit and miss fly by night jam session pick up circumstances. Going on strike doesn’t seem to improve things. Yet the U.S. empire is, in more ways than one, sitting on top of the world and would seem to have the capacity - if anyone would - to put into motion constructive and restorative initiatives on a remarkable scale. Is it really that these conditions are a reflection of a genuine lack of enough to go around?

Well, there can’t be any serious shortage of money. Besides all that startup capital in violently stolen land and labor, this 5% of the world’s people gobbles up a whole 1/3 of all of the planet’s resources; but, just a tiny 1% of these settlers owns and controls 40% of that pie. 10% owns almost 75% of it; and 4 out of 10 get to divvy up the leftover one-hundredth. Interesting.

So, what’s all this excess accumulation serving? Where, in practice, one dollar equals one vote, more is squandered on methods of mass murder and intimidation than the military expenditures made by the rest of the world; and, incidentally, more is spent on military bands than on the entire NEA. More, mostly underfunded, human beings are warehoused in those peculiar institutions of incarceration than anyplace else, while plenty of kids have got parents who are scuffling to get by while working double shifts. If folk values like hard work really did count, people doing slave labor would be the richest around.

What activities (and who) gets the money - and what doesn’t get the money - isn’t just some shoulder shrugging instance of “historical inevitability.” What gets cared for, and what doesn’t - which voices get heard and which don’t - are choices, and are, at larger scales, arguably social engineering. (Besides, why censor outright what attrition can dispose of better than half the time?) There’s more than one reason that, back in the invasion days (of North America, that is), even a lot of the Europeans who were adopted into indigenous communities refused to go back.

Well, Gandhi did think western civilization would be a good idea. What happens to music is just a very, very tiny part of the effect of these, um... suspect imbalances; and it’s useful to keep in mind that music has always functioned as a conduit of hope and continuity in the face of what are, in the long run, absolutely overwhelming odds.

The title, the drum is honor enough, is a translation from the Yoruba ayantola, which is also part of Dr. Juma Santos Ayantola, who was to have played dun dun on this recording had not the University of Ghana made him an offer he couldn’t refuse; but, most importantly, given Newman’s, Steve’s and Hill’s wonderful work, the title continues to suit the character and intent of the music: the drum is honor enough.

There was something of a gantlet to run leading up to this music’s arrival in the Spirit Room. I’d appointed myself to compose all this new music for the recording and to try to get beyond what I’d already done on which way what. The time frame wasn’t going to allow for the usual seasoning process with the band, but I took the leap anyway of organizing 5 compositions into more or less completed form in advance, which brought on at times a sensation of juggling 5 novels simultaneously, worrying myself over characters and plot development while trying to keep each story from bleeding over into the others. This was both unusual and absorbing.

I haven’t yet mentioned the audiences we’ve been playing for who’ve really moved me with their warmth, welcome, curiosity and enthusiasm. A good number of the listeners I got to talk with were intrigued that we were looking at these big charts as part of all the sounds they were hearing. They were interested in knowing how the music was put together and told me how they missed the old fashioned kind of liner notes that talked about the music instead of emphasizing notoriety. I feel a little ambivalent about wrapping too many words around the misteri in music because, for one thing, no string of descriptive or explanatory blablahblah can ever really be definitively on target. And, besides that, the poetry can’t be sensibly talked about at all, as the music does that telling. All considered, however, I can still relate a few practical descriptions of what’s happening behind the sounds of each track that will also be so partial and fragmentary that you shouldn’t allow them to at all define the music you’re hearing.

drums

not bombs

For the idea behind this title I have to thank Newman whom I once heard

contrasting the relative worth of significant Amercian contributions to

the world such as the trap kit and nuclear warfare. I began writing this

with a melodified imaginary 12 bar trap solo that dips around the quarter

note, dotted quarters and triplet quarters; and from that grew a rhythmically

contrary countermelody. Each little phrase is a song of its own, groups

of which are rearranged into other episodes with other ambiances.

hot

red

This is an almostslow drag that I discovered while playing around with

pyramiding shuffle phrases. A triplet quarter and a triplet eighth fit

inside a quarter note. A quarter and an eighth fit inside a dotted quarter.

A dotted quarter and a quarter fit inside a 5/8; and that plus a dotted

quarter fit into a whole note, and so forth. One idea suggested another

from there, and on and on.

shadow

doing

This one grows around the curving tones of a dun dun, which is played

here by NTB, as well as around a sound I’d heard in a dream.

rough

hue

This began both in response to a particularly fine Steve Coleman performance

as well as to an especially luminous silence on our recording of scissor

bump on the which way what CD. I wanted to construct a vamp cycle that

didn’t have the one being bashed to tears - as I was hearing the

drummer do that night with the Five Elements - and that would involve

instead a little more built-in balance shifting swerves and swells around

a gravitational pivot ala the Parker principle.

Rough Hue extends over what I call a round square (4:6:9 - also developed

on round square on the which way what CD). For each of these 3 tempos,

there’s a melody - each thinned out ala the Basie principle - that

together can be heard, in composite form, in the saxophone riff at the

beginning of the trombone solo. In the first section, the patterns are

pruned to emphasize these sneaky faux antiphonal canonic episodes. Besides

this, the improvisers have 2 interlocking hemiolas to work with - 4:6

(2:3) and 6:9 (2:3). Out of what would ordinarily be an 18 (3x6) beat

cycle, a beat’s dropped, making it a 6-5-6 cycle, which helps put

more of a stop time ripple across the soundscape. Sometimes, some of the

variations remind me of either classical Japanese or Shona motion, among

other associations.

permeations

gumvindaboloo

Listening back to this one, I think it really does want a bigger band;

but not having one at the moment - and the irresistible allure of hearing

where it all might go - prompted recording this first draft anyway. I’d

been savoring the effect of parade drums - in India’s Sryam Brass

Band - playing all those slick and quick little bangara figures in unison.

I found a place for that sensation incidentally while experimenting with

5:3, from which I developed most of the ideas - except for the deliberately

contrary ones. Many of the melodies were carved out of what I call a transparency

- except for when they aren’t. Imagine a melody 30 tones long, out

of which each rhythmic pattern finds its own melody, and when contrasting

patterns intersect, they do so at a melodic pitch unison as well. The

suite format is an adaptation to the current unwieldiness of the material,

but it turns out to have some possibilities after all. Oh, and on the

first section, that alto player chose to use a coffee cup instead of a

plunger mute.

What humanizes sound into music are communications, decisions, arguments and cooperations that can be inferred behind a sonic persona, all of which is, in a single word, drama. Jazz has the richest dramatic (not necessarily in the extraneous melodramatic or theatrical sense associated with some entertainment) possibilities of any music so far - between how it’s made and the methods of augmenting and underscoring extemporization that have been developed in the last hundred years or so - not to mention that living musical DNA that spirals all the way back to some time before Egypt and Nubia.

Much of the truth in our music emerges in the encounter between the musicians as protagonists with the music itself. Recorded here are the responses and inventions of Hilliard Greene, Steve Swell, Newman Taylor Baker, etc., who, once in the ring, contributed their share of exemplary nimble-be-quick to the fi-fo-fum of music that even the saxophonist had yet to hear. While we were packing up for the rush back to whatever-had-to-be-done-next in NYC, there was still music out there in the snow pounding on the windows trying to get in and be heard. But, then, it’s always like that. Just watch out for the rematch.

Dedications

To Bob Shechtman - composer, trombonist, bassist - with whom I studied for a couple of years in the 70’s and who recently went off and joined the sasha before could enjoy this. I’ll miss him. Among the many memorable perceptions he would share, he emphasized that many Byzantine mosaics included deliberately inserted wrong tiles in order to wake up the observer from going to sleep inside the patterns. He got me to take music so seriously that I haven’t been able to shake it loose since - and showed me much much more.

To the people of Haiti on the 200th anniversary of the beginning of their independence.

To Percy Schmeiser, the Saskatchewan farmer who stood up to the intrusions of the Monsanto syndicate.

To JSA who couldamightawouldashoulda.

Thanks

to

Steve Baczkowski, Newman Taylor Baker, Tola Brennan, Steve Cannon, Mark

Chistman, Kurt Ellenberger, Lisle Ellis, Hilliard Greene, Mike Hentz,

Donna Iannapolla, Robert Iannapolla, Eric Kline, Tom Kohn, Debbie Klaber,

Maureen Knighton, Chris Martin, Laura Martin, André Martinez, Fareed

Harvey McKnight, Gregg Moore, Dee Pop, Eileen Ressler, Bob Rusch, Juma

Santos Ayantola, the painter, Albert Simonson, Christopher Sullivan, Steve

Swell, Lazaro Vega.

-patrick brennan